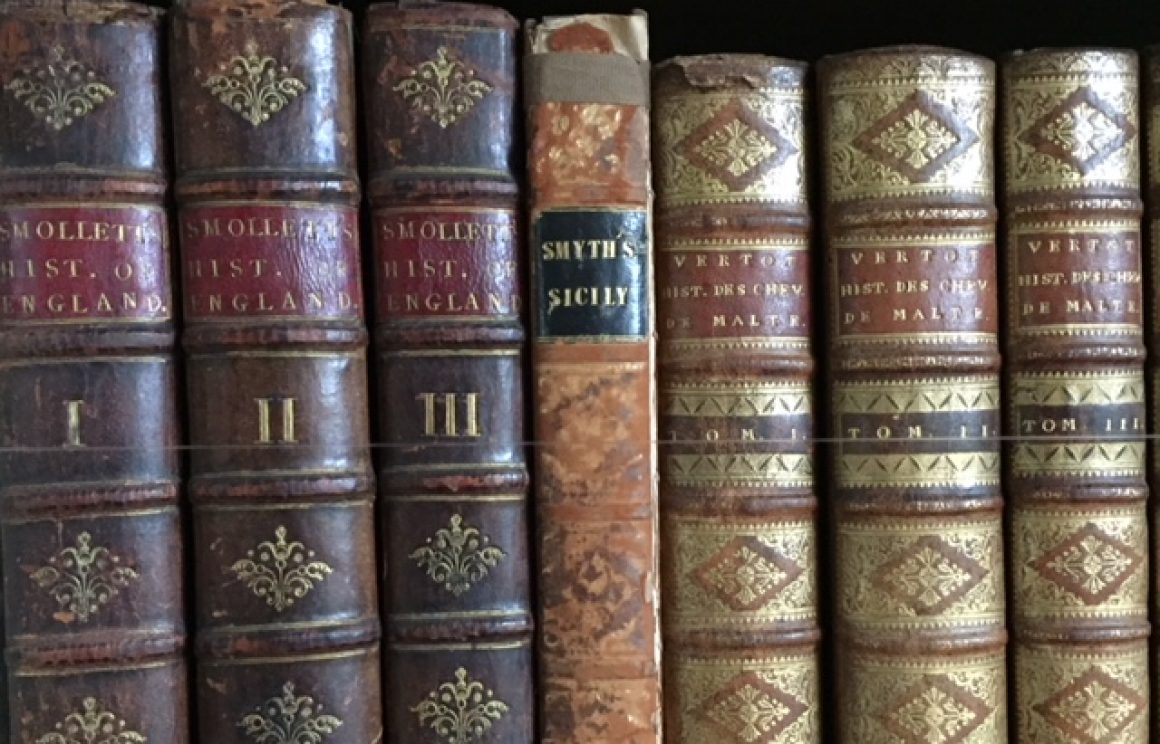

Book Cover

The Stone Boudoir

Travels Through the Hidden Villages of Sicily

Theresa Maggio

Perseus Publishing, 2002

ISBN 0-7382-0342-4

246 pages $25.00

Reviewed by Peat O’Neil

Theresa Maggio is a story teller. New Jersey born, the author is of Sicilian heritage and has lived in Sicily off and on for a considerable time, researching Mattanza, her book about tuna fishing. In this book, she returned to explore Sicily’s mountain villages.

Maggio steps behind the shuttered facades of crumbling Sicilian hill towns. Behind the gates and stone walls there’s vibrant culture and the ebb and flow of family life. Some women she meets are drowning in it, other women are thriving on the challenges of building professional careers as pharmacists or architects in a quixotic culture rooted in fidelity to feudal hierarchies and long dead saints..

The chapters describing her several visits to Santa Margherita form an image of stone everywhere – the houses, cool cellars, stone barns, caves where wine and food are stored. Also the embedded-in-granite way the women can be entombed alive, apparently willingly, in service to the family. Nella in the village never married, certain that “men just want a slave.” But she cares for her aunt full time and is a housewife in every way, though in a female household.

The writing is clear and straightforward. Maggio was previously a science writer and does not waste a reader’s time in self-indulgent digression. But if the narrative is lean, the telling is rooted in poetry and human emotion. By chapter three, you’re a member of the family peering over her shoulder at a plate of pasta while an older relative urges you to eat more. We’re back in the old country, in the remote hill towns where families gather for meals, unmarried adult children live with their parents and a biggest party is a saint’s feast day.

Maggio befriends many Sicilians during the course of her several visits — architects, pharmacists, artisans, café owners and farmers. The writing shines when she’s describing the landscape and the people. “We ascended past olive groves, hazelnut trees, and almond and pear orchards in bloom. We saw the deep-wrinkled necks of older farmers in straw hats who hacked at the soil between trees. March is the season for cultivation in the mountains of Sicily, before the sun gets too hot in April. I stuck my heard out the window and sniffed the air. Up here it was chilled champagne.”

If you look hard enough there are cooking recipes in the narrative “She added chopped walnuts and parsley to the veal and wrapped the mixture in triangular patches of pounded turkey cutlets. She poked holes in these and inserted tiny cubes of ham, then tied each packet up with string, ready for the frying pan.”

And instructions for making the polished stone mosaics “A pile of semiprecious stones ground flat and thin as crackers lay in the sunlight on the work table, their frosted colors full of promise: matte turquoise, lapis lazuli, … The stones interlocked like a jigsaw puzzle in a marble slab chiseled to hold them. Later he would polish the stone painting.”

The festival to St. Agatha in Catania in the shadow of Mt. Etna might be the high point in the narrative. “Every year on February 4 and 5, the men of Catania pull her relics, housed in bejeweled life-sized effigy, through the city’s streets for two days and two nights, the duration of her martyrdom. It is said to be the second largest religious procession in the world.. Half of the women here are named after her, but it is really a feast for the men, who have claimed the girl saint for their own.”

I hated to finish this superb book with characters fully sketched in their setting and scenes so real that even a reader who has never been to Sicily can absorb the way of life. I have traveled in Sicily by car, thumb, bus and train. It’s a wonderful place for the voyager with a knack for connecting with people and enjoying life.

Book review by L. Peat O’Neil, author of Pyrenees Pilgrimage and teaches writing for The Writer’s Center and UCLA.